Part I: Understanding the World of Snakes

An Introduction to Serpentes

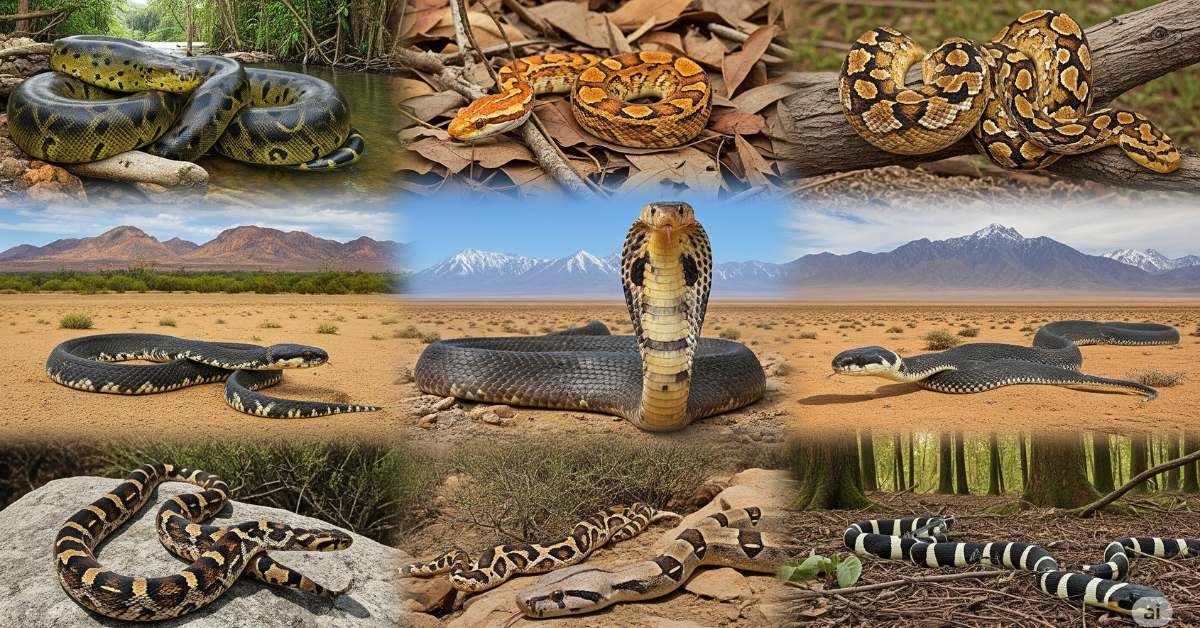

Snakes, belonging to the suborder Serpentes, are among the most evolutionarily successful and specialized vertebrates on the planet. Their limbless form, often a source of human fear and fascination, is a masterclass in adaptation, allowing them to thrive in nearly every ecosystem, from dense rainforests and arid deserts to freshwater rivers and even the open ocean. Their public perception is deeply polarized; they are simultaneously revered in cultural mythologies and reviled as symbols of danger. By examining their biology, behavior, and relationship with humanity, we can foster a more nuanced appreciation for these remarkable animals.

1.1 The Anatomy of a Snake: Unique Adaptations for Survival

The body of a snake is a marvel of biological engineering, stripped of limbs to achieve a form perfectly suited for its environment and predatory lifestyle. As ectothermic, or “cold-blooded,” creatures, snakes rely on external sources to regulate their body temperature, often basking in the sun to warm up and seeking shade or burrows to cool down.1 This dependence on ambient temperature dictates their daily and seasonal activity patterns, such as the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake’s shift from being active during the day (diurnal) in cooler months to active at night (nocturnal) during the heat of summer.2

A snake’s skin is covered in scales, which are not separate pieces but rather folds in the epidermis. These scales can be smooth and glossy, or they can feature a raised ridge down the center, a trait known as being “keeled”.3 This texture provides protection and aids in locomotion. Lacking eyelids, snakes have a transparent, protective scale over each eye called a brille, which shields the eye from dust and dirt and is shed along with the rest of the skin.2

Perhaps their most famous sensory tool is the forked tongue. When a snake flicks its tongue, it gathers scent particles from the air and ground, which are then delivered to the vomeronasal system, or Jacobson’s organ, located in the roof of the mouth.7 This advanced chemosensory ability allows them to track prey, find mates, and navigate their environment with remarkable precision.

Many of the snakes in this report possess an additional, highly sophisticated sensory organ: heat-sensing pits. In the pit vipers—a group that includes rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths—these loreal pits are located between the eye and the nostril on each side of the head.2 Pythons and anacondas have similar heat-sensing labial pits along their lips.1 These organs detect infrared radiation, allowing the snake to perceive a thermal image of its surroundings. This gives them a significant advantage in locating warm-blooded prey, especially in low-light conditions or complete darkness.1

The snake’s skull and jaw are uniquely adapted for consuming prey much larger than their own head. The lower jaw bones are not fused at the chin, and a special quadrate bone connects the jaw to the skull, allowing for an incredibly wide gape.7 This enables giants like the Green Anaconda and Burmese Python to swallow animals as large as deer, capybaras, and even caimans.11

1.2 Venomous vs. Non-Venomous: A Critical Distinction

A fundamental and often misunderstood aspect of snake biology is the difference between venomous and non-venomous species. These terms are not interchangeable. A venomous animal, such as a rattlesnake or cobra, injects toxins (venom) into another creature, typically through a bite or sting, as a method of predation or defense.6 In contrast, a poisonous animal is one that is toxic if ingested or touched. While most snakes fall into one category or the other, the common garter snake presents a rare case of being both. It produces a mild venom in its saliva and can also become poisonous by storing toxins in its liver from the newts it consumes.8

The venomous snakes featured in this report belong to two major families: Viperidae and Elapidae.

The Viperidae family includes the pit vipers, such as the Western and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes, the Copperhead, and the Cottonmouth. These snakes are characterized by their long, hollow, hinged fangs located at the front of the mouth, which fold back when not in use. Their venom is typically complex and primarily hemotoxic or cytotoxic, meaning it attacks the blood, circulatory system, and surrounding tissues, causing swelling, pain, and tissue destruction.

The Elapidae family includes the King Cobra and the Black Mamba.15 Elapids possess shorter, fixed fangs at the front of the mouth. Their venom is predominantly neurotoxic, targeting the nervous system. It works by disrupting the transmission of nerve signals, which can lead to paralysis, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest.15

The non-venomous snakes in this report—the Corn Snake, Ball Python, Burmese Python, and Green Anaconda—subdue their prey primarily through constriction.1 After striking and seizing the prey with their sharp, recurved teeth, they rapidly wrap their muscular bodies around the animal. The immense pressure they exert does not crush the prey but rather cuts off its blood flow and prevents it from breathing, leading to a quick and efficient death before the prey is swallowed whole.1

1.3 The Role of Snakes in the Ecosystem

Far from being mere pests or threats, snakes are integral components of healthy, balanced ecosystems, serving as crucial mid-level predators. Their primary ecological function is population control. By preying on a wide variety of animals, especially prolific species like rodents, they help to regulate prey populations and prevent overgrazing of vegetation.22 This service has direct benefits for humans, as snakes help to keep in check populations of animals often considered pests, which can damage crops and spread disease.7

Snakes are not only predators but also an important food source for a host of other animals. Birds of prey like hawks and eagles, mammals such as foxes and raccoons, and even other snakes depend on them for sustenance.8 Their position in the middle of the food web makes them a vital link, transferring energy from the small animals they consume up to the larger predators that consume them. The decline or removal of a snake species from an ecosystem can have cascading, negative effects, disrupting this delicate balance. The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, for instance, is considered a “keystone” species in its habitat, not only for its role as a predator but because the gopher tortoise burrows it uses for shelter are also essential refuges for over 300 other wildlife species.16 Its decline, therefore, threatens the stability of its entire ecological community.

1.4 Human-Snake Interactions: From Fear to Fascination

The relationship between humans and snakes is one of the most ancient and complex in the animal kingdom. It is a dynamic shaped by deep-seated fear, cultural reverence, scientific curiosity, and practical concerns over safety and conservation. This report explores snakes that are highly searched online, and the reasons for this interest are multifaceted.

Native venomous species like rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths generate significant search interest driven by public safety. People seek information on identification to distinguish them from harmless look-alikes, on their habitats to know where encounters are likely, and on safety protocols to prevent bites.3 In contrast, non-venomous snakes like the Corn Snake and Ball Python are popular largely due to their role in the pet trade. Searches for these species revolve around their docile nature, husbandry requirements, and the vast array of selectively bred color and pattern variations known as “morphs”.22

Exotic snakes, those not native to the searcher’s region, often capture the public imagination due to their superlative qualities. The King Cobra and Black Mamba are famous for their potent venom and formidable reputations, making them subjects of intense curiosity.15 The Green Anaconda and Burmese Python command attention for their sheer size, representing the upper limits of what a snake can be.1

Finally, some snakes, like the Burmese Python in Florida, become a focal point of public interest due to their status as invasive species. The ecological devastation they cause, coupled with the dramatic efforts to control their population, generates significant news coverage and public engagement, turning the snake into a symbol of a larger environmental crisis.29 This report will delve into each of these species, exploring the biological facts and the human stories that make them so compelling.

Part II: Profiles of Ten Remarkable Species

The American Vipers: Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, and Cottonmouths

The United States is home to a diverse array of snakes, but none capture public attention—and apprehension—quite like the native pit vipers. This group, belonging to the family Viperidae and subfamily Crotalinae, is defined by the presence of heat-sensing loreal pits that allow them to hunt with deadly accuracy. The three most-searched members of this family—rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths—are responsible for the vast majority of venomous snakebites in the country. Understanding these snakes is therefore a matter of both ecological appreciation and public safety. This chapter provides an in-depth profile of these iconic American vipers, focusing on their identification, behavior, and the realities of coexisting with them.

2.1 The Rattlesnakes: Icons of the Americas

Instantly recognizable by the chilling buzz of their tail, rattlesnakes are uniquely American serpents that have become powerful symbols of the wild frontier. Their specialized warning system, potent venom, and striking patterns make them objects of both fear and respect. Among the many species, the Western and Eastern Diamondbacks stand out for their size, prevalence, and impact on human-snake interactions.

2.1.1 Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake, Crotalus atrox, is arguably the most iconic snake of the American Southwest. Its prevalence in the region and its formidable reputation make it a frequent subject of human encounters and, consequently, scientific and public interest.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Western Diamondback is a heavy-bodied pit viper, easily identified by the series of 23-45 dark, diamond-shaped blotches that run down its back. These markings are set against a ground color that can vary from brown and beige to gray or pinkish, providing excellent camouflage in its arid environment. Its tail is distinctly marked with two to eight bold black and white bands, earning it the nickname “coontail”. This tail pattern is a key feature that helps distinguish it from other species like the Mojave rattlesnake, whose black tail rings are much narrower than the pale ones.

Like all pit vipers, it possesses a wide, triangular head that accommodates large venom glands.2 Its face is adorned with specialized sensory equipment: a pair of heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils for detecting warm-blooded prey, and vertically elliptical pupils suited for varying light conditions.2 Its eyes are protected by transparent scales called brilles, as the snake has no eyelids.2

The most famous feature is, of course, the rattle. Composed of hollow, interlocking segments of keratin, the rattle produces a sharp buzzing sound when vibrated, serving as a clear warning to potential threats.2 A new segment is added each time the snake sheds its skin; however, because older segments often break off, the number of rings is not a reliable way to determine the snake’s age.2 Adults typically grow to about 4 feet (120 cm) in length, though exceptional individuals can exceed 6 feet (180 cm), making it the second-largest rattlesnake species behind its eastern cousin.2

Habitat & Distribution

Crotalus atrox is native to the arid and semi-arid regions of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, with a range stretching from Southern California east to Arkansas. It is a highly adaptable species, thriving in a variety of habitats from flat coastal plains and sandy deserts to steep, rocky canyons and pine-oak forests. It can be found at elevations ranging from below sea level to as high as 6,500 feet (2,000 m). During the winter, these snakes retreat to hibernacula (dens) to brumate, often using rock crevices or taking over the burrows of other animals, particularly prairie dogs.

Behavior & Ecology

The Western Diamondback is a solitary creature, except during the spring mating season. Its daily activity is governed by temperature. In the cooler months of spring and fall, it is primarily diurnal, or day-active. As temperatures soar in the summer, it shifts to a nocturnal, or night-active, lifestyle to avoid the extreme heat.

It is an ambush predator, relying on its camouflage to lie in wait for prey. It uses its forked tongue to constantly sample the air, delivering chemical cues to its Jacobson’s organ to interpret its surroundings and locate prey.2 Despite its fearsome reputation, the Western Diamondback is not an aggressive snake. It prefers to avoid confrontation and will typically only strike if it feels cornered or directly threatened.2 Its first line of defense is its camouflage, followed by its rattle. A bite is a last resort. In the wild, its lifespan can be up to 20 years.2

Reproduction

This species is ovoviviparous, meaning the female retains the eggs inside her body until they hatch, effectively giving birth to live young. Following a gestation period of three to four months, she will give birth to a litter that averages around 14 young, known as neonates. The young are born fully equipped with fangs and venom and are independent from birth. However, the young population faces a high mortality rate during its first winter due to lack of food, freezing temperatures, and predation.

Venom and Human Interaction

The Western Diamondback is responsible for more venomous snakebites in North America than any other species. This is largely a function of its large population, wide distribution, and frequent proximity to human activity. However, a bite from this snake is rarely fatal. In fact, more people in the United States are killed by lightning strikes each year than by the bite of any venomous rattlesnake. This statistic underscores a critical point: while a bite is a serious medical emergency requiring immediate hospital care, the danger is often survivable with modern medical treatment.

2.1.2 Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus)

The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, Crotalus adamanteus, is a truly impressive reptile. As the largest rattlesnake in the world and one of the heaviest venomous snakes in the Americas, it commands a presence matched by few other serpents. Unfortunately, this magnificent animal is also one of the most threatened, facing a dramatic decline across its native range.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The sheer size of the Eastern Diamondback is its most striking feature. While average adults measure four to five feet, they can reach lengths approaching eight feet and weigh over 15 kg (34 lbs). Its body is exceptionally heavy and stout. The snake is named for the bold, diamond-shaped markings on its back. These patterns, typically centered with black or brown, are crisply outlined in a brilliant yellow, standing out against an olive, dusty gray, or blackish-brown ground color. The belly is generally a yellowish or off-white color. Like its western counterpart, it is a pit viper with a large, triangular head, heat-sensing pits, and a prominent rattle on its tail.

Habitat & Distribution

The historical range of the Eastern Diamondback covers the southeastern coastal plains of the United States, from southeastern North Carolina, south through the Florida peninsula, and west to eastern Louisiana. Its preferred habitats are dry, upland ecosystems, particularly longleaf pine savannas, pine and palmetto flatwoods, and sandhill environments with turkey oak.

This species is deeply connected to the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus). The deep burrows excavated by these tortoises provide the rattlesnake with essential refuge from temperature extremes and fire.16 This relationship makes the gopher tortoise a “keystone species”; its survival is critical to the survival of the rattlesnake and over 300 other species that also use its burrows.16 The decline of longleaf pine forests and gopher tortoise populations has therefore had a devastating, direct impact on the Eastern Diamondback.33 While primarily a terrestrial snake, it is also an excellent swimmer and will venture into marshy habitats, sometimes crossing miles of open water between the mainland and barrier islands.17

Behavior & Ecology

The Eastern Diamondback is a classic sit-and-wait ambush predator. It will often find a promising location, such as along a game trail, and lie in a tight coil for hours or even days, waiting for prey to pass. They are primarily terrestrial and not adept climbers, but they have been occasionally spotted in bushes and trees, sometimes as high as 10 meters (33 feet) off the ground, likely in search of prey.

Their disposition can vary significantly. Some individuals will allow a close approach without reacting, while others will begin rattling their tail from a distance of 20 to 30 feet.17 When threatened, they will raise the front half of their body off the ground in a defensive S-shaped coil, ready to strike a distance of up to one-third of their body length.17 They will often hold their ground, but if given an opportunity, they prefer to retreat.9 A common and dangerous misconception is that they must rattle before striking; they are fully capable of striking silently.17 Unlike many other rattlesnake species that congregate in communal dens, Eastern Diamondbacks typically hibernate alone in stump holes or tortoise burrows.33

Diet & Reproduction

The diet of an adult Eastern Diamondback consists mainly of small mammals, with rabbits (both Eastern cottontails and marsh rabbits), rats, and squirrels being primary food sources. They will also eat ground-dwelling birds like bobwhite quail and towhees. Due to their large size, adults can easily consume a fully grown cottontail rabbit. After striking its prey, the snake releases it and follows the scent trail of the dying animal.

Reproduction is a slow process for this species, a factor that contributes significantly to its vulnerability. Females are ovoviviparous and breed only once every two to four years.17 After a gestation of six to seven months, they give birth to a litter of between 4 and 28 live young, typically in the late summer or early fall.16 The young are born looking like miniature adults, but with a small “button” on their tail instead of a full rattle.16 They stay with their mother for only a short period (10-20 days) before dispersing on their own.17

Venom and Human Interaction

The Eastern Diamondback is widely considered the most dangerous venomous snake in North America. This reputation is due to a combination of factors: its large size, which allows it to store a massive amount of venom; its long fangs, which can be over an inch long in a large specimen and can deliver a deep injection; and its high venom yield, averaging 400–450 mg in a single bite. For context, the estimated lethal dose for a human is only 100–150 mg.

The venom is a complex and destructive cocktail of toxins. It contains a thrombin-like enzyme (“crotalase”) that causes blood to clot, leading to a rapid depletion of clotting factors and a risk of internal bleeding.17 It also contains components that are highly hemorrhagic (causing bleeding) and necrotizing (causing tissue death), as well as a peptide that can interfere with neuromuscular transmission and potentially lead to cardiac failure.16 A bite causes immediate and severe pain, described as feeling like “two hot hypodermic needles,” followed by intense swelling, discoloration, and bleeding from the wound and mouth.17 Historically, untreated bites had a mortality rate as high as 30%, though modern antivenom (like CroFab and Anavip) has made fatalities much rarer.17

Conservation Status

The contrast between this snake’s formidable power and its fragile conservation status is stark. While the IUCN still lists the species as “Least Concern,” this assessment is dated, and the population trend is noted as declining. On the ground, the situation is dire. The species is now believed to represent only 3% of its historical numbers and is currently under review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for protection under the Endangered Species Act. It is already listed as endangered in North Carolina and is considered extirpated (locally extinct) in Louisiana, with the last sighting there in 1995.

The primary threats are human-caused. Habitat loss is the most significant, as the longleaf pine savannas they depend on have been cleared for agriculture, urban development, and pine plantations.34 The decline of the gopher tortoise has also eliminated their essential overwintering refuges.34 Direct persecution is another major factor; thousands are killed on roads and out of fear each year.17 The commercial skin trade also takes a heavy toll, fueled by “rattlesnake roundups,” events where snakes are collected from the wild.34 A particularly destructive collection method involves pouring gasoline into tortoise burrows to flush the snakes out, a practice that poisons the burrow and harms the many other species that rely on it.36 While some roundups have transitioned to educational festivals, others continue to promote the killing of these snakes.34 Conservation efforts are focused on habitat restoration through prescribed burning, protecting gopher tortoise populations, public education, and translocation programs to move snakes from development sites to protected areas.34

The plight of the Eastern Diamondback serves as a powerful illustration of a key conservation principle. Its decline is not just the story of a single species but an indictment of the health of its entire ecosystem. This snake, a specialist tied to a specific and dwindling habitat, is far more vulnerable than a generalist species that can adapt to human-altered landscapes. This contrast is vividly demonstrated by the next snake in our report, the Copperhead. While the Diamondback struggles for survival, the Copperhead thrives, often in the very suburban environments that have replaced the Diamondback’s native forests. This difference underscores that an animal’s ecological role and adaptability are as crucial to its survival as any physical defense it may possess.

2.2 The Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)

The Copperhead, Agkistrodon contortrix, is one of the most frequently encountered venomous snakes in eastern North America. Its willingness to live in close proximity to humans, combined with its superb camouflage, makes it responsible for a high number of snakebites annually. However, a closer look reveals a creature that is far less dangerous than its reputation suggests and a remarkable example of adaptation and survival.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Copperhead is a medium-sized, thick-bodied pit viper, typically averaging two to three feet in length. Its most defining feature is its coloration and pattern. The head is a solid, unmarked coppery-tan color, which gives the snake its common name. The body’s background color can range from a light tan or pinkish-tan to a richer reddish-brown. This is overlaid with a series of dark, chestnut-brown crossbands shaped like an hourglass or dumbbell.3 These bands are distinctively narrow across the snake’s spine and flare out to become wide on its sides. This pattern provides exceptional camouflage among the leaf litter of its forest floor habitat.

Juvenile copperheads are similar to adults but are often grayer in color and possess a vibrant, sulfur-yellow tail tip.3 This brightly colored tail is not just for show; the young snake wiggles it like a worm to lure unsuspecting prey, such as frogs and lizards, within striking distance—a behavior known as caudal luring.37 This yellow tip fades with age, disappearing by the time the snake is three or four years old.3

As a pit viper, it has all the hallmarks of the family: heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, vertically elliptical pupils, and keeled scales.3 Its venom is delivered through a pair of fangs that are periodically replaced throughout its life.3

Habitat & Distribution

The Copperhead is a true habitat generalist, a key reason for its success and abundance. Its range is extensive, covering a vast portion of the eastern and central United States, from southern New England south to the Florida panhandle, and west to Nebraska and Texas.

Unlike specialists such as the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, the Copperhead is not tied to a single ecosystem. It thrives in a wide variety of environments, including deciduous forests, mixed woodlands, rocky hillsides, and swampy, low-lying regions.3 Its adaptability extends to human-modified landscapes; copperheads are commonly found in abandoned sawdust piles, around old farms and barns, at construction sites, and even in wooded suburban neighborhoods.3 During the winter, they brumate in dens or limestone crevices, often sharing these hibernacula with other species, such as timber rattlesnakes and black rat snakes.37

Behavior & Ecology

The Copperhead’s behavior is dictated by the seasons. It is typically diurnal (active during the day) in the milder weather of spring and fall, but becomes nocturnal (active at night) to avoid the heat of the summer months.

Its primary defense strategy is to rely on its near-perfect camouflage. When a potential threat approaches, a copperhead’s first instinct is not to flee but to “freeze” and remain perfectly still, blending in with the leaves and soil.37 This behavior, while effective at avoiding predators, is a major reason why so many people are bitten. An individual can unknowingly step on or place a hand near a motionless copperhead, provoking a defensive strike.3 They are generally non-aggressive snakes and will almost never bite unless they are touched, stepped on, or otherwise physically provoked. If given a chance, they will try to slither away quietly.3 When agitated, they will vibrate their tail rapidly, which can produce a buzzing sound in dry leaves, and may gape to show the inside of their mouth as a warning.37

Diet & Reproduction

The Copperhead is an opportunistic, generalist feeder with a broad diet. As ambush predators, they will take up a promising position and wait for suitable prey to wander by Juveniles, using their yellow-tipped tails as lures, tend to eat more invertebrates and small ectotherms (cold-blooded animals) like caterpillars, cicadas, frogs, and lizards. Adults shift their diet to include more endothermic (warm-blooded) prey, such as voles, shrews, chipmunks, and mice of the genus Peromyscus.26 However, both young and old will eat opportunistically. They are also known to climb into bushes and trees to hunt for freshly molted cicadas.3

Copperheads are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young.37 Mating occurs in the spring and fall. Females can store sperm over the winter, allowing for fertilization the following spring.38 After a gestation period of several months, a female will give birth to a litter of one to 20 young, with four to seven being typical.37 In a remarkable display of reproductive flexibility, copperheads are also capable of facultative parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction where a female can produce offspring without a male.37

Venom and Human Interaction

Due to its abundance and tolerance for suburban habitats, the Copperhead is responsible for more venomous snakebites in many states than any other species. In North Carolina, for instance, they are thought to account for over 90% of all venomous bites.

Despite the frequency of bites, the consequences are rarely severe. Copperhead venom is among the least potent of all North American pit vipers, and fatalities are exceptionally rare.3 They often deliver “warning bites” with little to no venom injected, a phenomenon known as a “dry bite”.37 A bite is certainly painful and requires immediate medical attention, with symptoms including intense pain, tingling, throbbing, and significant swelling.37 However, the risk of life-threatening complications is very low. Interestingly, research has identified a protein in their venom called

contortrostatin, which has shown promise in animal studies for its ability to halt the growth and spread of cancer cells, highlighting the potential medicinal value hidden within snake venoms.37

Conservation Status

The Copperhead is listed as a species of “Least Concern” by the IUCN, with a population trend considered stable. Their success is a direct result of their adaptability. As habitat generalists, they are able to survive and even thrive in the fragmented and altered landscapes created by human development, a stark contrast to habitat specialists like the Eastern Diamondback. While they face localized threats from habitat destruction and direct persecution by humans, their overall population is secure.

2.3 The Cottonmouth / Water Moccasin (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

The Cottonmouth, known scientifically as Agkistrodon piscivorus and colloquially as the Water Moccasin, is a semi-aquatic pit viper that inhabits the wetlands of the southeastern United States. It is a snake steeped in folklore and fear, often burdened with a reputation for aggression that is not supported by scientific observation. Understanding the true nature of this powerful predator is key to safely coexisting with it in its watery domain.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Cottonmouth is a large, keeled-scaled, and exceptionally heavy-bodied snake, with adults typically measuring between two and four feet, though some individuals can grow larger. Its head is large, broad, and triangular, with prominent jowls that house its venom glands. A dark line runs through the eye on each side of the head.

Coloration in cottonmouths is notoriously variable. Juveniles and some adults can be beautifully marked with dark, wide crossbands on a brown or yellow background.5 However, as they age, many cottonmouths darken significantly, with older individuals often appearing as a uniform, solid brown or black, obscuring the pattern entirely.5 Like the Copperhead, juvenile cottonmouths have a bright yellow or greenish tail tip that they use as a lure for prey.4

The snake’s most famous characteristic, and the source of its name, is the stark white interior of its mouth.4 When threatened, it will often gape its mouth wide open in a defensive display, revealing this “cottony” lining.5 A key feature for identifying a cottonmouth in the water is its swimming posture. It is a very buoyant swimmer and typically holds its head up and out of the water, with most of its body visible on the surface.4 This is a useful way to distinguish it from the many species of harmless, non-venomous water snakes (genus Nerodia), which are often mistaken for cottonmouths but tend to swim with more of their body submerged.5

Habitat & Distribution

The Cottonmouth’s range extends throughout the southeastern United States, from the coastal plains of southeastern Virginia, south through Florida, and west to central Texas and southeastern Kansas. As a semi-aquatic species, it is almost always found in or near freshwater. It can inhabit nearly any freshwater environment but is most common in cypress swamps, river floodplains, marshes, and heavily vegetated wetlands. They are also known to venture into brackish waters and salt marshes and can be found on offshore islands.4 While they are tied to water, they will travel overland, especially during droughts, to migrate between wetlands.

Behavior & Ecology

The aggressive reputation of the Cottonmouth is one of the most persistent myths in North American herpetology. Multiple scientific studies have shown that this characterization is false. When confronted by humans in the wild, their first instinct is to try to escape. If escape is not possible, they will resort to a highly intimidating threat display. This display typically involves coiling their body, vibrating their tail, making a loud hiss, and throwing their head back to gape with their mouth wide open. They may also flatten their body and release a pungent musk from their anal glands.

A bite is a last resort. Research has shown that cottonmouths will seldom bite unless they are physically touched, stepped on, or picked up.5 The perception of aggression often arises because a threatened cottonmouth may retreat toward the nearest cover, which can sometimes be in the direction of the human that startled it, giving the false impression of a “charge”.18

They can be active day or night, but in the heat of summer, they forage primarily after dark.5 They bask on logs, rocks, or low-hanging branches at the water’s edge but, unlike harmless water snakes, they rarely climb high into trees.5

Diet & Reproduction

The Cottonmouth is a highly opportunistic and generalist predator. Its carnivorous diet is incredibly varied and includes fish, frogs, lizards, other snakes (including smaller cottonmouths), small turtles, baby alligators, birds, and small mammals. They are one of the few snakes known to scavenge, sometimes eating carrion. They are particularly adept at exploiting drying pools in wetlands, where they will congregate to feed on fish and amphibians that have become trapped. In a fascinating recent development, cottonmouths in Florida have been observed preying on the invasive Burmese Python, suggesting they may be adapting to hunt this new and abundant food source.

Like other American vipers, the Cottonmouth is ovoviviparous.18 Mating typically occurs in the spring or early summer, and males will engage in “combat dances” to compete for females.5 Females give birth to a litter of 1 to 20 live young every two to three years.4

Venom and Human Interaction

A bite from a cottonmouth is a serious medical event. Their venom is more potent than that of a copperhead and is powerfully cytotoxic, meaning it is very destructive to tissue.18 While deaths from cottonmouth bites are extremely rare, the venom can cause severe pain, swelling, ecchymosis (bruising/discoloration), and significant tissue necrosis (death). In severe cases, this tissue damage can lead to permanent scarring and, on rare occasions, may necessitate amputation of the affected digit or limb. Unlike the venoms of some rattlesnakes or elapids, cottonmouth venom generally does not cause systemic or neurotoxic effects. Bites are effectively treated with CroFab antivenom.

Conservation Status

The Cottonmouth is currently listed as a species of “Least Concern” by the IUCN and is considered common in many parts of its range.5 However, this status does not mean it is free from threats. Like many wetland-dependent species, it is vulnerable to habitat loss and fragmentation caused by the drainage of swamps and marshes for agriculture and development. Furthermore, due to its fearsome (and largely undeserved) reputation, it is frequently killed by people out of fear or misidentification. In Indiana, at the northern edge of its range, the cottonmouth is listed as an endangered species.

The Gentle Constrictors and Common Natives

Shifting from the venomous vipers that command cautious respect, this chapter explores a different side of the serpentine world. Here, the focus is on snakes renowned not for their venom, but for their docile nature, popularity in the pet trade, or their status as common, harmless residents of backyards across North America. The Corn Snake and Ball Python represent the pinnacle of the herpetocultural hobby, while the Garter Snake is one of the most familiar and widespread snakes on the continent. These species offer a window into the world of responsible pet ownership, the complexities of conservation law, and the gentle nature of most snakes.

3.1 The Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus)

The Corn Snake, Pantherophis guttatus, is a vibrant, slender snake that has become one of the most popular reptilian pets in the world. Its calm temperament, manageable size, and stunning variety of colors make it an ideal entry point for aspiring herpetologists, while its role in the wild highlights the ecological benefits of snakes.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

Also known as the Red Rat Snake, the Corn Snake is a non-venomous constrictor belonging to the family Colubridae. Adults typically average between 30 and 48 inches (about 2.5 to 4 feet), though some individuals can grow to be nearly 6 feet long. They have a relatively slender build. A unique feature is their body shape, which is like a loaf of bread in cross-section—flat on the bottom and rounded on top—an adaptation that aids in climbing.

The “classic” or wild-type Corn Snake is a beautiful animal. Its dorsal side has a background color of orange, reddish, gray, or brownish, which is overlaid with large, prominent reddish-brown blotches bordered in black.22 The belly is what truly sets it apart, featuring a bold, black-and-white checkerboard pattern.22 There are two main theories for its common name: one suggests the belly pattern resembles the kernels of flint corn (also known as Indian corn), while the other posits that they were frequently found in corn cribs and barns, where they hunted the rodents that fed on stored grain.22

Habitat & Distribution

The Corn Snake is native to the eastern and central United States, with a range extending from southern New Jersey down to the Florida Keys, and westward into Louisiana and parts of Kentucky.22 They are an incredibly adaptable species, capable of thriving in a wide variety of habitats. They are commonly found in wooded groves, on rocky hillsides, in overgrown fields, and palmetto flatwoods. They are also well-adapted to living near humans and are often found in and around barns, abandoned buildings, and farms, where they find ample prey and shelter.

Behavior & Ecology

Corn Snakes are secretive and spend a great deal of their time hidden from view. They can be found hiding under loose tree bark, beneath logs and rocks, or moving through the underground burrows of the rodents they hunt. They are excellent climbers and will readily ascend trees or the walls of buildings in search of a meal. While generally active during the day (diurnal), they may become more active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) during the hottest parts of the year.

When threatened, a Corn Snake may exhibit a behavior intended to mimic a more dangerous snake. It will vibrate its tail rapidly in dry leaves, creating a buzzing sound that can be mistaken for the warning of a rattlesnake.22 This defensive bluff, combined with their reddish, blotched pattern, often leads to them being misidentified as and killed for being venomous Copperheads.22

Diet & Reproduction

As constrictors, Corn Snakes subdue their prey by coiling their muscular bodies around it and suffocating it before consumption. Their diet in the wild is varied and includes small rodents, lizards, frogs, birds, and even bats.22 They are highly beneficial to humans as they help control pest populations.

Corn Snakes typically breed in the spring, from March to May.22 A month or so after mating, the female lays a clutch of 10 to 25 leathery-shelled eggs.22 She seeks out a warm, damp, and sheltered location, such as a rotting stump, a pile of decaying vegetation, or a sawdust pile, which will act as a natural incubator for the eggs.22 After laying, the female abandons the eggs, providing no further parental care. The eggs incubate for about two months before hatching, with the small hatchlings using a special “egg tooth” to slit their way out of the shell.22

Pet Ownership & Legality

The Corn Snake is one of the most popular and widely kept pet snakes, second only to the Ball Python. This popularity is well-earned. They are generally very docile, tolerate handling well, have relatively simple care requirements, and remain a manageable size. Decades of captive breeding have resulted in a staggering array of “morphs”—selectively bred variations in color and pattern, such as “Amelanistic” (lacking black pigment), “Anerythristic” (lacking red pigment), and “Snow” (a combination of the two). This captive breeding industry has been so successful that it has largely eliminated the need for wild collection for the pet trade, which was a threat in the past.

The legal status of owning a Corn Snake can be surprisingly complex, a paradox that arises from its status as a native species in many parts of the U.S. While exotic species like the Ball Python are often less regulated, states with native Corn Snake populations may impose strict rules to prevent the poaching of wild animals. For example, Georgia law prohibits keeping native species as pets, which includes Corn Snakes, regardless of whether they were captive-bred.43 Virginia limits the number of Corn Snakes an individual can own without a specific permit 45, and Maryland requires permits for the possession of any native reptile.47 These laws, while sometimes frustrating for hobbyists, are designed to protect wild populations by removing the “I bought it” loophole for those who might illegally take snakes from the wild. This legal landscape underscores the critical importance for any prospective owner to thoroughly research their specific state and local regulations before acquiring a snake.

Conservation Status

The overall population of Corn Snakes is considered stable, and they are not federally protected. However, they do face localized threats. In some areas, such as the Florida Keys, they are listed as a species of special concern due to habitat loss. Across their range, their greatest threat is direct persecution by humans who mistake them for venomous Copperheads and kill them out of fear. Education about snake identification is therefore a key component of their conservation.

3.2 The Ball Python (Python regius)

The Ball Python, Python regius, has risen to become the most popular pet snake in the world, cherished by keepers for its manageable size, calm disposition, and the incredible diversity of its captive-bred morphs.28 Native to Africa, this small python’s fame is built on its unique and endearing defensive behavior, from which it derives its name.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

Also known as the Royal Python, the Ball Python is the smallest of the African pythons. It has a distinctly stocky and muscular build, with a relatively small head for its body size and smooth scales.28 Adults typically reach a length of three to five feet, with females generally being larger than males.

The wild-type or “normal” coloration consists of a black or dark brown background with large, irregular light brown blotches along the back and sides.28 The belly is typically a cream or off-white color, often scattered with black markings.28 Like other pythons, they are non-venomous constrictors and possess heat-sensitive pits along their lips that help them detect warm-blooded prey in the dark.1

Habitat & Distribution

The Ball Python is native to the grasslands, savannas, and sparsely wooded areas of West and Central Africa.7 Its range extends from Senegal east towards Sudan and Uganda. They are often found in areas near open water, where they can cool themselves, and they spend much of their time in the abandoned burrows of mammals or other underground hiding places.

Behavior & Ecology

The Ball Python is renowned for its docile and shy nature.1 Its name comes from its primary defense mechanism: when threatened or frightened, it coils itself into a tight ball, tucking its head and neck securely into the center. This “balling” behavior is employed in lieu of biting, making them one of the most tractable and easy-to-handle snakes in captivity.

They are primarily nocturnal or crepuscular, meaning they are most active at night, dawn, and dusk.7 During the day, they remain hidden in their burrows to rest and avoid predators. In the wild, males tend to exhibit more semi-arboreal (tree-climbing) behaviors, while the heavier females are more terrestrial.28

Diet & Reproduction

In their native habitat, Ball Pythons are ambush predators that feed mostly on small mammals and birds. Their diet includes rodents such as Gambian pouched rats, gerbils, and shaggy rats. After consuming a meal, they will often remain in the warm, dark burrow of their prey for several days to digest.

Ball Pythons are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs.28 A female will lay a clutch of three to eleven large, leathery eggs, typically in a concealed, underground location.28 She will then coil around the eggs, and through a process of muscular contractions known as “shivering,” she can generate heat to help incubate them.1 Once the eggs hatch after about 55 to 60 days, the mother’s parental care ends, and the hatchlings are left to fend for themselves.1 They are also one of the snake species in which parthenogenesis, or asexual reproduction, has been observed.28

Pet Ownership & Legality

The Ball Python’s placid temperament has made it the undisputed king of the reptile pet trade. They are bred in captivity on a massive scale, and this industry has produced an astonishing variety of “morphs.” Through selective breeding, keepers have isolated genetic mutations that alter color and pattern, resulting in over 7,500 different named morphs, from albinos and piebalds to more complex combinations.

This phenomenon, however, also highlights the ethical responsibilities of captive breeding. One of the most popular patterns, the “spider” morph, is inextricably linked to a neurological condition known as “wobble syndrome.” Snakes with this gene often exhibit symptoms ranging from a mild head tremor to severe disorientation and lack of coordination, where they struggle to right themselves.28 The intentional breeding of an animal with a known genetic defect for purely aesthetic reasons has sparked significant debate within the herpetological community. In response to these welfare concerns, organizations like the International Herpetological Society have banned the sale of spider morphs at their sanctioned events, signaling a growing movement toward more ethical breeding practices.28

Regarding legality, because Ball Pythons are an exotic (non-native) species in the United States, their ownership is often less restricted than that of native snakes like the Corn Snake. However, some jurisdictions have enacted broad, sweeping laws out of fear or for ease of enforcement. New York City, for example, has a blanket ban on the ownership of all python and boa species, which includes the small and harmless Ball Python.50 This illustrates the importance for potential owners to check not only their state laws but also their specific city or county ordinances.

Conservation Status

The Ball Python presents a conservation paradox. It is incredibly common in captivity, yet it faces significant threats in its native African range. It is currently listed as “Near Threatened” on the IUCN Red List. The primary driver of its decline in the wild is poaching for the international pet trade, where thousands are captured and exported annually. Wild-caught individuals often carry parasites and struggle to adapt to captivity, frequently refusing to eat. The species is also hunted for its skin and for use as bushmeat. This situation highlights a disconnect between the captive hobby and wild conservation, where the immense popularity of the species as a pet directly contributes to the pressures on its wild populations.

3.3 The Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis)

The Common Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis, is one of the most familiar and widely distributed snakes in all of North America. Often encountered in gardens, parks, and near local ponds, it is for many people their first, and most frequent, interaction with a wild snake. Its adaptability and abundance make it a keystone of many local ecosystems.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

Garter snakes are small to medium-sized snakes with a slender body, typically growing to between two and four feet long.6 Their appearance is highly variable across their vast range and among their many subspecies, but the most common pattern consists of three light-colored longitudinal stripes on a darker background. These stripes can be yellow, greenish, blue, or white, and they run the length of the snake’s body against a background of black, brown, or olive. Many also have a checkered or spotted pattern between the stripes. Their scales are keeled (possessing a central ridge), giving them a slightly rough texture, and they have large, round pupils.

Habitat & Distribution

The Common Garter Snake is a testament to adaptability, boasting one of the most extensive ranges of any reptile in the Western Hemisphere. It is found from the subarctic plains of Canada south through the United States and into Central America. They are absent only from the most arid desert regions of the American Southwest.

They thrive in a multitude of habitats, including meadows, forests, woodlands, fields, and grasslands.8 The one near-constant is their proximity to water. They are almost always found near a water source, such as a pond, stream, marsh, or even a drainage ditch, as much of their diet consists of aquatic and amphibious creatures.6 Their ability to live in suburban and urban parks and gardens makes them a common sight for many people.6

Behavior & Ecology

Garter snakes are primarily diurnal, or day-active. They are social animals that communicate using complex pheromonal trails. They can follow the scent trails of other garter snakes to locate them for mating or to find communal dens.8 In colder climates, they brumate (the reptilian form of hibernation) through the winter, often in enormous groups. These communal hibernacula can contain hundreds or even thousands of snakes, which gather from miles around.

When disturbed, a garter snake’s first instinct is often to flee, sometimes diving into nearby water to escape a threat. If cornered, it may coil and strike, but it is more likely to engage in defensive behaviors like hiding its head while flailing its tail.8 Its most notable defense is the release of a foul-smelling, musky secretion from glands near its cloaca, a pungent deterrent to would-be predators.8

Diet & Reproduction

Garter snakes are carnivorous generalists with an exceptionally broad diet. They will eat almost any creature they are able to overpower.8 Their diet commonly includes earthworms, slugs, leeches, amphibians (like frogs and salamanders, including their eggs), small fish, and rodents.6 They are one of the few predators of the toxic rough-skinned newt and have evolved a resistance to its potent tetrodotoxin.

They are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young.6 After mating in the spring, females give birth in late summer to large litters that can range from a dozen to as many as 80 neonates, though 12-40 is more typical.6

Venom and Human Interaction

For centuries, garter snakes were considered completely non-venomous. However, discoveries in the early 2000s revealed that they do, in fact, produce a mild neurotoxic venom in their saliva, delivered by enlarged teeth in the back of their mouth. However, this discovery does not change their status as harmless to humans. They lack an efficient venom delivery system (like the fangs of a viper) and produce only a tiny amount of very mild venom. A bite from a garter snake cannot seriously injure or kill a person; at worst, it might cause minor, localized itching or swelling.6

In a fascinating biological twist, garter snakes can also be poisonous. When they consume toxic newts, they can sequester the tetrodotoxin in their liver for weeks, making their own bodies poisonous to any predator that might try to eat them. This makes them one of the very few animals in the world that are both venomous and poisonous.8

Conservation Status

As a species, the Common Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) is abundant and widespread. It is listed as “Least Concern” by the IUCN and is considered globally secure (G5) by NatureServe.55 However, this broad classification masks the peril faced by some of its unique subspecies. Conservation status must often be examined at a more granular level to be meaningful.

The most notable example is the San Francisco Garter Snake (T. s. tetrataenia), considered one of the most beautiful snakes in North America with its stunning turquoise belly and red and black stripes.52 This subspecies is federally listed as an Endangered species and is protected by the state of California.52 Its population has been decimated by the destruction and fragmentation of its wetland habitat due to urbanization, as well as by illegal collection for the pet trade.52 Similarly, the Narrow-headed Garter Snake (Thamnophis rufipunctatus), a distinct species, has seen its population decline due to the introduction of non-native sport fish and crayfish that prey on the snake and its food sources.8 These examples demonstrate that even for a species as common as the garter snake, specific populations and subspecies can be pushed to the brink of extinction, highlighting the importance of localized conservation efforts and habitat protection.

The Global Superstars: Cobras, Mambas, and Giant Constrictors

While the previous chapters focused on snakes native to the United States, public curiosity knows no borders. The digital age has brought the world’s most spectacular and fearsome reptiles into our homes, generating immense interest in species that most people will never encounter in the wild. This chapter profiles the global superstars: snakes that have earned worldwide fame for their record-breaking size, their lethal venom, or their dramatic impact on ecosystems far from their native lands. From the snake-eating King Cobra of Asia to the lightning-fast Black Mamba of Africa, and from the invasive Burmese Python to the colossal Green Anaconda, these are the snakes of legend and headline news.

4.1 The King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah)

The King Cobra, Ophiophagus hannah, is a snake that inspires awe and commands respect. As the world’s longest venomous snake, it is a dominant predator in its Asian forest home, possessing a unique combination of intelligence, power, and surprising parental care. Its iconic status makes it a focal point for both fear-based persecution and vital conservation efforts.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The King Cobra is a truly majestic serpent, with an average length of 10 to 13 feet and a record length of over 18 feet (5.85 m). Despite its common name and its ability to raise its body and spread a hood like other cobras, it is not a “true cobra” of the genus

Naja. Instead, it is the sole member of its own genus, Ophiophagus, a name derived from Greek that translates to “snake-eater,” a direct reference to its specialized diet.21

Its coloration is variable across its wide range, from olive-green and tan to brown or black, often marked with faint, yellowish or white cross-bars or chevrons.15 The throat is typically a light yellow or cream color.15 When threatened, the King Cobra puts on one of the most impressive defensive displays in the animal kingdom. It can raise the front third of its body straight off the ground—sometimes to the eye level of a human—while flattening its long, narrow hood and emitting a low-pitched hiss that has been described as a “growl”.15

Habitat & Distribution

The King Cobra has a vast distribution across South and Southeast Asia. It is found from India and southern Nepal, east through southern China and the Philippines, and south throughout the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia. It is a creature of the forest, preferring to live in dense or open woodlands, bamboo thickets, and dense mangrove swamps, almost always in close proximity to a stream or other body of water.

Behavior & Ecology

The King Cobra is an intelligent, diurnal predator that primarily hunts during the day. It uses its forked tongue to track the scent trails of its prey with great efficiency. Despite its formidable reputation, the King Cobra is generally a shy and reclusive snake that prefers to avoid humans. When encountered, its first instinct is to flee. It will only become aggressive and stand its ground if it is cornered or provoked.

The one major exception to this rule is a nesting female. In a behavior unique among all snakes, the female King Cobra builds an above-ground nest for her eggs.15 Using her body to gather and pile up leaves and twigs, she constructs a mound that can be over three feet wide at the base.21 The decomposition of the vegetation inside the mound generates heat, helping to incubate the eggs. The female will then remain on or near the nest, guarding it with extreme aggression, and will not hesitate to attack any animal—including humans—that approaches too closely.15

Diet & Reproduction

As its scientific name implies, the King Cobra is a specialist predator whose diet consists almost entirely of other snakes.15 It is an apex predator among serpents, hunting and eating large rat snakes, pythons, and even other venomous snakes like kraits and other cobras.15 When food is scarce, it may occasionally take other vertebrates like lizards or birds.

After mating, the female lays a clutch of 21 to 40 eggs in the nest she has constructed.15 She guards them for the incubation period of 60 to 90 days. The venom of the hatchlings is just as potent as that of the adults from the moment they are born.21 The average lifespan of a King Cobra in the wild is about 20 years.21

Venom and Human Interaction

The venom of the King Cobra is extremely potent and is delivered in large quantities. A single bite can deliver enough venom to kill an adult elephant. The venom is primarily neurotoxic, attacking the central nervous system and, specifically, the respiratory centers in the brain.15 A bite is a dire medical emergency. Symptoms appear rapidly and progress from vertigo and blurred vision to paralysis, cardiovascular collapse, and coma. Without immediate and proper medical treatment with antivenom, death from respiratory failure can occur in as little as 30 minutes.

Conservation Status

The King Cobra is listed as a “Vulnerable” species on the IUCN Red List. It faces two primary threats, both caused by humans: habitat destruction and direct persecution. Across its range, the forests it depends on are being cleared for agriculture, timber, and urban expansion. At the same time, it is often killed on sight by people who fear its deadly reputation. It is also poached for its skin, meat, and for use in traditional medicine.

This status as a powerful yet vulnerable predator illustrates a key concept in modern conservation: an animal’s position at the top of the food chain offers no protection from human-induced threats. The survival of the King Cobra depends entirely on managing human behavior and protecting its habitat.

In response to these threats, inspiring conservation initiatives have emerged, particularly in India and Nepal. These programs recognize that the key to saving the snake is to work with the local communities who share its habitat. Organizations like the Eastern Ghats Wildlife Society in India and the Save The Snakes team in Nepal have pioneered community-led conservation models.60 These efforts include training local “snake saviors” to safely rescue and relocate cobras from human habitations, running educational programs in schools to dispel myths and reduce fear, and establishing community-based nest protection programs where locals are empowered to guard nesting sites.60 By using the charismatic King Cobra as a flagship species, these projects aim to protect not just the snake, but the entire rainforest ecosystem upon which it, and the local human populations, depend.63

4.2 The Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis)

The Black Mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, is a name that evokes a potent combination of fear and fascination. Native to Africa, it is renowned for its speed, unpredictable nature, and highly toxic venom, earning it a reputation as one of the world’s deadliest snakes. While much of this reputation is deserved, it often overshadows the true nature of this remarkable elapid.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Black Mamba is the longest venomous snake in Africa and the second-longest in the world, surpassed only by the King Cobra. It is a long and slender snake with a distinctive coffin-shaped head. Adults typically range from 6 to 10 feet (2 to 3 m), but exceptional specimens have been recorded at lengths of 14 to 15 feet (4.3 to 4.5 m).

Contrary to its name, the snake’s external color is not black. Its scales are typically a shade of olive, grayish-brown, or gunmetal gray.19 The name “Black Mamba” comes from the inky-black coloration of the interior of its mouth, which it displays prominently as part of its threat display.19

Habitat & Distribution

The Black Mamba inhabits a wide range across sub-Saharan Africa, from Burkina Faso in the west to Ethiopia and Somalia in the east, and south to South Africa. It is an adaptable species that prefers moderately dry environments. It is commonly found in light woodland, scrubland, rocky outcrops, and semi-arid savanna. It will also inhabit moist savanna and lowland forests, but is not typically found at very high altitudes.

Behavior & Ecology

The Black Mamba is a versatile snake, equally at home on the ground (terrestrial) and in trees (arboreal). It is a diurnal species, active during the day, when it can be seen basking in the sun or actively foraging for prey.19 It often establishes a permanent lair in a termite mound, abandoned burrow, or rock crevice, to which it will return regularly.

The mamba is famous for its speed. It is the fastest land snake in the world, capable of moving at speeds up to 12 mph (20 km/h) over short distances.20 However, it is crucial to understand that this speed is used exclusively for escape, not for hunting.20 The Black Mamba is a nervous and skittish snake. In the wild, it will almost always seek to flee from a perceived threat and will rarely allow a human to approach closer than about 40 meters (130 feet).19

Its reputation for aggression stems from its behavior when it is cornered and its escape route is blocked. In this situation, it will put on a formidable threat display. It rears up, spreads a narrow neck-flap, gapes its mouth to reveal the black lining, and hisses loudly.19 If the threat does not retreat, the snake will not hesitate to strike, often delivering multiple bites in rapid succession.19 Its ability to raise a significant portion of its body off the ground allows it to strike at a human’s upper body.19

Diet & Reproduction

The Black Mamba is an ambush predator that primarily preys on small, warm-blooded vertebrates.19 Its diet includes birds (especially nestlings), rodents, bats, and small mammals like hyraxes and bushbabies. It typically bites its prey once, releases it, and then waits for the fast-acting venom to paralyze the animal before swallowing it.

Black Mambas are oviparous, laying a clutch of 6 to 17 eggs in a warm, sheltered location.19 There is no parental care after the eggs are laid. The hatchlings are venomous from birth and can grow rapidly, reaching up to 2 meters (6.5 feet) in their first year.19

Venom and Human Interaction

The Black Mamba is classified by the World Health Organization as a snake of medical importance, and for good reason.19 Its venom is a potent, fast-acting cocktail of neurotoxins, primarily dendrotoxins, which are unique to mambas. Symptoms of envenomation can appear within 10 minutes and progress with terrifying speed. Early signs include a metallic taste in the mouth, drooping eyelids, and slurred speech, which quickly advance to difficulty breathing, paralysis, and loss of consciousness. A bite from a Black Mamba can cause a human to collapse within 45 minutes, and without prompt and aggressive treatment with antivenom, death from respiratory failure is almost certain, typically occurring within 7 to 15 hours. Before the widespread availability of antivenom, a bite from this species was considered 100% fatal.

Conservation Status

Despite its fearsome reputation, the Black Mamba is not currently considered to be at risk of extinction. It is listed as a species of “Least Concern” by the IUCN.19 This classification is based on its extremely wide distribution across sub-Saharan Africa and the fact that there is no evidence of a significant, widespread population decline.

However, localized threats do exist, primarily from habitat encroachment as human populations expand.66 A unique and inspiring conservation story related to this snake’s name is that of the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit in South Africa. Founded in 2013, this was the world’s first predominantly all-female anti-poaching unit.67 These women, who patrol unarmed, act as a deterrent to poachers through “visual policing” and are deeply involved in community education through their “Bush Babies” program.67 By protecting the reserve’s wildlife, including rhinos, they serve as powerful role models, demonstrating that conservation and community empowerment can go hand in hand, and that the war on poaching is won not with guns, but with education and social inclusion.67

4.3 The Burmese Python (Python bivittatus)

The Burmese Python, Python bivittatus, is a biological paradox. In its native Southeast Asia, it is a magnificent giant facing threats from habitat loss and over-harvesting. In South Florida, it is a destructive invader, an ecological catastrophe that serves as one of the world’s most dramatic examples of the dangers of invasive species. This dual identity makes the Burmese Python a compelling case study in globalization, conservation, and ecological disruption.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Burmese Python is one of the largest snake species on Earth.1 In their native range, they have been documented reaching lengths of up to 23 feet (7 meters), though individuals in Florida’s invasive population typically average between 6 and 9 feet. The largest captured in Florida measured over 18 feet long. They are powerful, non-venomous constrictors with a stocky body that can be as wide as a telephone pole in large specimens.

Their pattern is distinctive: a tan-colored body overlaid with dark, irregular blotches that look like puzzle pieces or giraffe markings.70 The head is pyramid-shaped and features a dark, arrowhead-shaped wedge pointing toward the nose.70 Like other pythons, they have heat-sensing pits along their lips to help them locate warm-blooded prey.1

Native Habitat & Distribution

The Burmese Python is native to a large swath of Southeast Asia, including countries like Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and parts of India and southern China. In this region, they are highly adaptable, inhabiting a range of ecosystems from rainforests and swamps to grasslands and marshes, often near freshwater sources.

The Florida Invasion: A Case Study in Ecological Disaster

The story of the Burmese Python in Florida is a cautionary tale for the 21st century. The species is not native to the Americas, but a breeding population became established in South Florida, primarily in and around Everglades National Park. This invasion originated from the exotic pet trade in the 1980s. As these snakes grew to unmanageable sizes, many were intentionally or accidentally released into the wild by overwhelmed owners. The problem was catastrophically amplified in 1992 when Hurricane Andrew, a powerful Category 5 storm, destroyed a python breeding facility, releasing countless snakes into the adjacent Everglades ecosystem.

The subtropical climate of South Florida proved to be a perfect match for the python’s needs. With a high reproductive rate (females can lay clutches of up to 100 eggs), rapid growth, and a lack of natural predators, their population exploded.30 Conservative estimates now place their numbers in the tens of thousands, with some suggesting the population could be as high as 300,000.1

The ecological impact has been nothing short of devastating. As a new, highly efficient apex predator, the Burmese Python has decimated native wildlife populations. A landmark 2012 study by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) revealed the shocking scale of the damage. In areas where pythons were well-established, populations of raccoons had declined by 99.3%, opossums by 98.9%, and bobcats by 87.5% since 1997.29 Marsh rabbits, cottontail rabbits, and foxes had effectively vanished from these areas.29

The pythons are generalist predators, consuming a huge variety of mammals, birds, and reptiles. They have been documented eating over 84 different native species, including federally protected species like the endangered Key Largo woodrat and the threatened wood stork, and are even capable of killing and eating American alligators.30 This rampant predation disrupts the entire food web, robbing native predators like the endangered Florida panther of their food sources.75

The pythons have also introduced new diseases. They are carriers of a parasitic lungworm, Raillietiella orientalis, which has now “spilled over” and is infecting native Florida snakes.72 There is also concern that by altering the predator-prey dynamics, they could indirectly affect the spread of mosquito-borne illnesses. One study found that with the disappearance of small mammals (the usual hosts for mosquitoes), the insects have shifted to feeding on rodents, which may be more fertile hosts for the Everglades virus.30

The economic cost of this invasion is immense. The United States spends billions of dollars annually managing invasive species, and millions have been specifically allocated to python control in Florida.76 In 2023, the Florida state budget allocated over $3 million for python removal and research efforts.78

In response, a multi-agency effort is underway to manage the python population. The Burmese Python has been listed as an “Injurious Species” under the federal Lacey Act, which prohibits their importation into the U.S..70 In Florida, they are a “Prohibited” species, and they can be humanely killed on private and many public lands year-round without a permit or hunting license.70 Management strategies include the “Python Patrol,” a program that trains the public to identify, report, and safely handle pythons, and research into new control tools like pheromone traps.71

The most high-profile control effort is the annual Florida Python Challenge®. Started in 2013, this 10-day event invites both professional and novice hunters to compete for cash prizes for removing the most and the longest pythons.82 The challenge serves a dual purpose: removing hundreds of pythons from the ecosystem and, perhaps more importantly, raising public awareness about the profound threat of invasive species.82 Since 2000, over 22,000 pythons have been removed from Florida, but controlling the vast, cryptic, and rapidly reproducing population remains a monumental challenge.83

Conservation Status

The Burmese Python’s status is a stark illustration of how context defines a species’ relationship with humans. In its native range in Southeast Asia, it is listed as “Vulnerable” by the IUCN. There, its populations are declining due to habitat loss and over-harvesting for the skin trade, traditional medicine, and the very pet trade that led to its introduction elsewhere. In Florida, it is one of the most destructive invasive species in North America, a creature whose removal is actively encouraged and funded by state and federal governments. This single species is simultaneously a conservation target in one part of the world and a target for eradication in another—a powerful symbol of the unintended ecological consequences of a globalized world.

4.4 The Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

The Green Anaconda, Eunectes murinus, is a serpent of mythical proportions. As the heaviest snake in the world, and one of the longest, this South American giant reigns as an apex predator in the flooded forests and grasslands it calls home. Its immense size and power have made it the subject of countless legends and a symbol of the untamed Amazon.

Identification & Physical Characteristics

The Green Anaconda holds the undisputed title of the world’s most massive snake. While the Reticulated Python of Asia may achieve slightly greater lengths, the Anaconda is far bulkier and heavier due to its incredible girth, which can be over a foot in diameter. Females are significantly larger than males, a phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism. An average adult female can be 18 feet (5.5 m) long, but they can reach lengths of up to 30 feet (9 m) and weigh more than 550 pounds (250 kg).

They are members of the boa family and are non-venomous constrictors.13 Their coloration provides excellent camouflage in their murky aquatic habitat. The body is a dark olive-green to brown, overlaid with large, circular black blotches along the back.13 The sides are adorned with smaller oval spots that have yellow centers.11 In a key adaptation for their aquatic lifestyle, their eyes and nostrils are positioned on the very top of their head, allowing them to see and breathe while the rest of their enormous body remains submerged and hidden from view.11

Habitat & Distribution

The Green Anaconda is native to the tropical lowlands of South America, found east of the Andes mountains. Its range includes the vast Amazon River basin in Brazil, the Orinoco River basin in Colombia and Venezuela, and the seasonally flooded Llanos grasslands.

They are a semi-aquatic species, spending most of their lives in or around water.90 They prefer swamps, marshes, and slow-moving rivers and streams over swift currents.13 While they are incredibly powerful and stealthy in the water, their immense bulk makes them slow and cumbersome on land.13

Behavior & Ecology

Anacondas are primarily nocturnal ambush predators.14 They lead a solitary life, lurking in the murky water and waiting for prey to come to the water’s edge to drink.91 When an unsuspecting animal comes within range, the anaconda strikes with incredible speed, seizing the prey in its jaws.92 It then uses its immensely powerful body to coil around the victim, killing it by constriction before swallowing it whole.

During the dry season in habitats like the Llanos, when water sources may disappear, anacondas will either migrate to find remaining water or burrow deep into the mud, where they can enter a state of dormancy (aestivation) until the rains return.87

Diet & Reproduction

As an apex predator, the Green Anaconda has an extensive and impressive diet. It is an opportunistic carnivore that will eat almost any animal it can manage to overpower. Juveniles feed on smaller prey like fish, frogs, and birds. Adults, however, are capable of taking truly formidable prey. Their diet is known to include large rodents like the capybara (the world’s largest rodent), deer, tapirs, wild pigs (peccaries), birds, and other reptiles like turtles and caimans.

There are documented cases of anacondas preying on caimans, powerful crocodilians in their own right.95 In a testament to their power, there are also reports of them killing and eating jaguars, though such events are likely rare.23 The relationship between anacondas, caimans, and jaguars is complex; they are all apex predators that can be both predator and prey to one another depending on the size and circumstance of the encounter.96 After consuming a very large meal, an anaconda’s slow metabolism allows it to go for weeks or even months without needing to eat again.13

Anacondas are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young after retaining the eggs inside their body.14 Mating occurs in the water, often in a spectacular event where multiple smaller males form a “breeding ball” around a single large female.90 After a gestation period of six to seven months, the female gives birth to a large litter of 20 to 40 young, though as many as 100 have been reported.14

Venom and Human Interaction

Green Anacondas are non-venomous. Due to their immense size, they are one of the few snakes in the world physically capable of consuming a human. While there are many local legends and unsubstantiated stories of anacondas eating people, and a few reports of unsuccessful attacks, there are no verified, documented cases of a Green Anaconda preying on a human. Their primary threat comes from humans. They are often killed out of fear or to protect livestock, and they are also hunted for their skin.

Conservation Status

The Green Anaconda is currently listed as a species of “Least Concern” by the IUCN. Its vast, remote, and often inaccessible habitat in the Amazon and Orinoco basins means that its population is likely large and relatively stable. However, it does face threats from human activity, including persecution and habitat degradation from deforestation, oil drilling, and the construction of hydroelectric dams. Recently, a 2024 genetic study proposed that the Green Anaconda may actually be two distinct species: the southern green anaconda (E. murinus) and a newly named northern green anaconda (E. akayima).104 If this split is accepted by the scientific community, it could have significant conservation implications, as the newly defined northern species would have a much smaller range and could potentially be at greater risk.87

Part III: Synthesis, Safety, and Stewardship

The detailed profiles of these ten remarkable snakes reveal a world of incredible adaptation, complex behavior, and deeply intertwined relationships with humanity. From the deserts of Arizona to the rainforests of the Amazon, and from the wild to the suburban backyard, these animals challenge our perceptions and demand our respect. This final section synthesizes the key themes from the species profiles into practical, actionable guidance. It addresses the most critical aspects of human-snake interaction: understanding and responding to the risk of venomous snakebites, the responsibilities of pet ownership, and the shared duty of conservation in a rapidly changing world.